For the last 75 years products (both durable goods and software) were built via Waterfall development. This process forced companies to release and launch products by model years, and market new and “improved” versions.

In the last few years Agile and “Continuous Deployment” has replaced Waterfall and transformed how companies big and small build products. Agile is a tremendous advance in reducing time, money and wasted product development effort – and in having products better match customer needs.

But businesses are finding that Continuous Deployment not only changes engineering but has ripple effects on the rest of its business model. And these changes may have unintended consequences leading to customer dissatisfaction and confusion.

Smart companies will figure out how to educate their customers and communicate these changes.

—-

The Old Days – Waterfall Product Development

(skip this part of you’re conversant in Waterfall and Lean.)

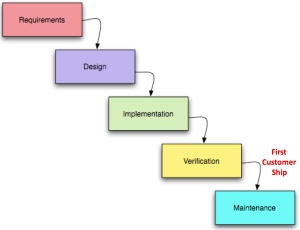

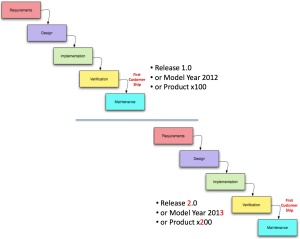

In the past both hardware and software were engineered using Waterfall development, a process that moves through new product development one-step-at-a-time.

- Marketing delivers a “requirements” document to engineering.

- Then engineering develops a functional specification and designs the product.

- Next comes the work of actually building the product – implementation.

- Then validation ensures the product was built to spec.

- After the product ships, it’s maintained by fixing flaws/bugs.

Customers would get their hands on a product only after it had gone through a lengthy cycle that could take years – enterprise software 1-2 years, new microprocessors 2-4 years, automobiles 3-5 years, aircraft a decade.

Waterfall – The Customer View

When customers purchased a product they understood that they were buying this year’s model. When next year’s model arrived, they did not expect that the Ford station wagon or Maytag washer they purchased last year would be updated to match all the features in the new model. (Software at times had an upgrade path, often it required a new purchase.)

Waterfall allowed marketers to sell incremental upgrades to products as new models. First starting in the fashion business, then adopted by General Motors in the 1920’s annual model year changeovers turned into national events. (The same strategy would be embraced 75 years later by Microsoft for Windows and then Apple for the iPhone.)

As the press speculated about new features, companies added to the mystique by guarding the new designs with military secrecy. Consumers counted the days until the new models were “unveiled”.

With its punctuated and delineated release cycles, waterfall development led consumers to understand the limited rights they had to future product upgrades and enhancements (typically none.) In other words, consumer expectations were bounded.

At the same time, manufacturers used new model changeovers to generate excitement over new features/versions convincing consumers to obsolete perfectly functional products and buy new ones.

Agile Development: Continuous Delivery and Deployment

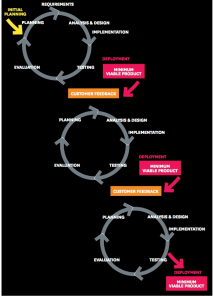

In contrast to Waterfall development, Agile Development delivers incremental and iterative changes on an ongoing basis.

Agile development has upended the familiar consumer expectations and company revenue models designed around the release cycles of Waterfall engineering. In a startup this enables deployment of Minimum Viable products at a rapid pace. For companies already in production, Continuous Deployment can eliminate months or years in between major releases or models. Companies can deliver product improvements via the cloud so that all customers get a better product over time.

While continuous delivery is truly a better development process for engineering, it has profound impacts on a company’s business model and customer expectations.

Continuous Delivery/Deployment – The Marketers View

Cloud based products has offered companies an opportunity to rethink how new business models would work. Adobe and Tesla offer two examples.

Tesla

While most of the literature talks about continuous Delivery/Deployment as a software innovation for web/mobile/cloud apps, Tesla is using it for durable goods – $100,000 cars – in both hardware and software.

First, Tesla’s Model S sedan downloads firmware updates on a regular basis. These software changes go much further than simply changing user interface elements on the dashboard. Instead, they may modify major elements of the car from its suspension to its acceleration and handling characteristics.

Secondly, in a break from traditional automobile practices, rather than waiting a year to roll out annual improvements to its Model S, Tesla has been continuously improving its product each quarter on the assembly line. There are no model years to differentiate a Tesla Model S built in 2012 from one built this year. (The last time this happened in auto manufacturing was the Ford Model T.)

Adobe

Adobe, which for decades sold newer versions of its products – Photoshop, Illustrator, etc. – has now moved all those products to the cloud and labeled them the Adobe Creative Cloud. Instead of paying for new products, customers now buy an annual subscription.

The move to the cloud allowed Adobe to implement continuous delivery and deployment. But more importantly the change from a product sale into a subscription turned their revenue model into a predictable annuity. From an accounting/Wall Street perspective it was a seemingly smart move.

Continuous Delivery/Deployment – The Customer View

But this shift had some surprises for consumers, not all of them good.

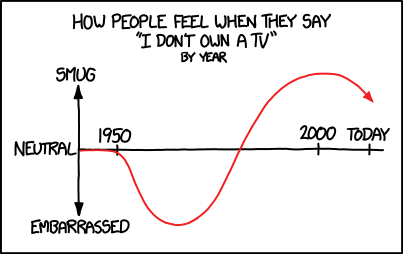

As many companies are discovering, incremental improvement doesn’t have the same cachet to a consumer as new and better. While it may seem irrational, inefficient and illogical, the reality is that people like shiny new toys. They want newer things. Often. And they want to be the ones who own them, control them and decide when they want to change them.

Adobe

While creating a predictable revenue stream from high-end users, Adobe has created two problems. First, not all Adobe customers believe that Adobe’s new subscription business model is an improvement for them. If customers stop paying their monthly subscription they don’t just lose access to the Adobe Creative Suite software (Photoshop, Illustrator, etc.) used to create their work, they may lose access to the work they created.

Second, they unintentionally overshot the needs of students, small business and casual users, driving them to “good-enough” replacements like Pixelmator, Acorn, GIMP for PhotoShop and Sketch, iDraw, and ArtBoard for Illustrator.

The consequence of discarding low margin customers and optimizing revenue and margin in the short-term, Adobe risks enabling future competitors. In fact, this revenue model feels awfully close to the strategy of the U.S. integrated steel business when they abandoned their low margin business ot the mini-mills.

Tesla

What could go wrong with making a car incrementally better over time? First, Tesla’s unilateral elimination of features already paid for without consumers consent is a troubling precedent for cloud connected durable goods.

Second, Telsa’s elimination of model years and its aggressive marketing of the benefits of continuous development of hardware and software have set its current customers expectations unreasonably high. Some feel entitled to every new hardware feature rolled into manufacturing, even if the feature (i.e. faster charging, new parking sensors,) was not available when they bought their cars – and even if their car isn’t backwards compatible.

Model years gave consumers an explicit bound of what to expect. This lack of boundaries results in some customer disappointment.

Lessons Learned

- Continuous Delivery/Deployment is a major engineering advance

- It enables new business models

- Customers don’t care about your business model, just it’s effect on them

- While irrational, inefficient and illogical, people like shiny new toys

- Subscription revenue models versus new purchases require consumer education

- If your subscription revenue model “fires” a portion of your customers, it may enable new competitors

- Companies need to clearly communicate customer entitlements to future features

Filed under: Customer Development, Marketing, Tesla